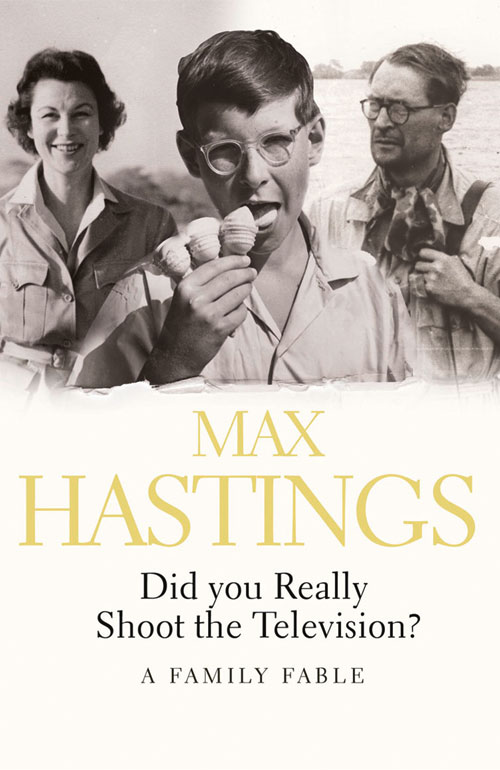

Almost all of us are intrigued by our own heredity. In this book, I’ve recounted the picaresque little saga of mine. The Hastingses weren’t at all important people, but they did some extraordinary and sometimes pretty weird things. And because they were writers for three generations, they wrote them down. When I did BBC’s Desert Island Discs back in 1986, I was pretty discreet about our tumultuous rows and my admittedly pretty awful childhood behaviour. But when my mother, Anne Scott-James, was DID’s guest at the age of 90 in 2003, to the audience’s delight and my toe-curling embarrassment, she regaled Sue Lawley with some horror stories, not least about my doings. For weeks afterwards, people came up to me in petrol stations and other unlikely places, asking: ‘Ere- did you really shoot the television ?’. It’s because people seemed intrigued by that question that I made it the title of this book. I’ll explain it in due course, but I want to make plain immediately that the victim was not a big set.

Mother liked to say: ‘all families are dysfunctional’, but ours managed to be more dysfunctional than most. When she was a mere stripling of 85, one day at lunch she demanded with her customary abruptness: ‘You still haven’t forgiven me for your childhood, have you ?’. I said she was quite wrong about that- one should judge things by how they turn out. Most of my own life has been uncommonly fulfilled. I probably inherited from her whatever talents I possess. But I added: ‘if you try a different question- did I enjoy my childhood ?- the answer’s ‘no’. When I was three or four, I doubt that you and I would have recognised each other in an identity parade’. Mummy paused for a moment, brooding. Then she said: ‘Whoever did you hear of who did anything with their lives who had’- the next bit in tones of withering scorn- ‘a happy childhood ?’

Most of us know what she means, though I doubt that her view deserves to be included in a child-rearing manual. In many ambitious people there is a strand of anger, and often it derives from the fact that we did not have exactly the upbringing or schooldays we thought we’d ordered. Today I’ll suggest a piece of social advice: if you are struggling for conversation with your neighbour at a dinner party, turn to them and say: ‘Do tell me about your ghastly childhood’. In eight cases out of ten, they will still be spouting away an hour later. In my case, I nowadays realise, I was a pretty awful child, with no idea how to behave. If I didn’t have a happy childhood, it was my own fault.

A few weeks ago I was interviewed for a magazine by the great Lynn Barber, who asked: ‘Have you ever considered psychotherapy ?’. Rather dismayed by this sally, I said: ‘What on earth for ?’. ‘To get over your ridiculous obsession with your father. Judging from your book, your mother was wonderful and your father ought to have been in some sort of home’. She was right, of course, that as a child I adored daddy- who signed himself Macdonald Hastings or Mac. Only slowly did I realise that he was pretty mad. He made his name as a war correspondent for the legendary magazine Picture Post, and went on to become a well-known writer and broadcaster. When I was a teenager, he gave me two pieces of advice, one sensible and the other characteristically not. First, he urged me to explore what he called ‘the challenge of a blank sheet of paper’ As a bored teenager, I had no idea what he meant. But when I became a writer, I understood perfectly. To this day, I feel a surge of excitement each morning as I look into an empty screen which it’s my happy responsibility for fill. Father’s other pearl of wisdom was less convincing. One evening- after, I am sorry to say, his usual daily half-bottle of gin- he told me I should marry a girl with fat legs, ‘because they are better in bed’. At 16 I’d had no opportunity to explore the virtues of girls of any dimensions. And even today, as both the girls to whom I have been lucky enough to be married have very thin legs, I still haven’t the slightest idea whether he was right.

When I was six, father became a star of Eagle, a famous comic of the 1950s, with the title of Eagle Special Investigator. Each week, he described real-life experiences, of a kind which thrilled a generation of schoolboys, and of course me. Many journalists would have been mortally embarrassed to perform pantomime stunts to amuse children. Never so Mac. In print as in life, his brand of innocence rendered him impervious to blushes. His success in the role was rooted in the fact that his readers understood that he loved every moment of being paid to fulfil fantasies. He crossed the Kalahari desert and was taught to fly a Tiger Moth biplane dressed in the approved manner of Biggles, with leather helmet and sheepskin flying-jacket.

As a circus knife-thrower’s target, he wrote, ‘stripped to the waist I stood against the board, feeling like any paleface in a Redskin encampment. Hal Denver swung his flaming hatchets in the air and performed a sort of war dance. I pressed my bare back against the splintered board and held my hands locked together in front of me as tightly as if I were bound at the wrists. I shall never forget the swish of those hatchets. They flew towards me, spinning through the air in flaming arcs, and the blades bit into the wood with force enough to fell a tree’. On St.Moritz’s Cresta toboggan Run a few weeks later, he described himself ‘hanging on for dear life and swinging round a bank of ice like a wall of death’.

He was forerunner of a legion of modern television hosts who stunt in the same fashion, though I doubt whether any enjoys their experiences as much as he did. In the later 1950s he went on to become a star of the famous BBC TV Tonight programme with the likes of Alan Whicker and Fyfe Robertson. He was a passionate romantic, who sought to teach me that to be born British was to draw the finest card in the pack of life. He blossomed most eloquently and convincingly when speaking of the English countryside. ‘Turnip’ Townsend and Coke of Norfolk vied for supremacy in his personal pantheon with Marlborough and Wellington. He perceived the development of English agriculture as a glorious pageant, matching our historic battlefield triumphs over such lesser races as the French. ‘Foreigners give the English credit for three things’, he mused, in a characteristic passage of his writings, ‘the beauty of our children, the lushness of our pasture and the mettle of our horses. Why is it, then, that when all three are brought together, we who speak Shakespeare’s tongue call the occasion a gymkhana ?’.

For all father’s success he was always broke, because he forged a self-image as a country gentleman journalist, which he fulfilled without a moment’s thought about the limits of his overdraft. His suits came in profusion from Savile Row, along with handmade shoes and boots to fit every venue from the ballroom to the hunting field, though he hated dancing and rode to hounds only a dozen times. A passing introduction to some activity investigated for Eagle induced father to equip himself in a fashion that would have impressed Mr.Toad. Jammed into cupboards in our London flat and Berkshire cottage were archer’s bows and arrows, falconers’ hoods and gauntlets, ferreters’ nets and lines, lassos and cowboy chaps, driving whips and top hats. Most of these accessories were used or worn but once, until I got my sticky and unauthorised little fingers on them.

Father was seldom at home, but spasmodically lunged into playing the good parent. In 1953, when I first departed sobbing towards prep school, he started a custom which persisted through the years which followed. On the first day of term, before we left for the station he took me to lunch, occasionally accompanied by my mother, at one of his favourite London restaurants. We started with the Caprice, then as now in Arlington Street, but much plusher in the ‘fifties. Father introduced me to the head waiter, solemnly assuring me that Mario would become one of the most important people in my life. He pointed out David Niven, Noel Coward and other stars at neighbouring tables. None of this spoiling treatment prevented me from bursting into tears. I recognised an attempt to bribe me into acquiescence about boarding the grimy school puffer at Paddington, and was not to be cajoled out of well-justified sulks. But the gastronomic round had two consequences. First, along with the rest of father’s programme of conspicuous consumption, it convinced me we must be pretty rich, a fantasy which went uncorrected until I was 15 or 16. Second, and more usefully, it supplied motivation. I became determined that, as an adult, I would enjoy the same standard of living, whatever drastic steps it took to achieve it.

When father, in conversation, wove dreams for my future, such an outcome was taken for granted. He talked with unflinching assurance about ‘when you play your first salmon…when you find yourself standing in a grouse butt in a gale…when you join the Beefsteak Club’. He cautioned me about the etiquette of never signing my name in any book which I might give someone as a present, until I was its author. He introduced me to tailors, bootmakers and head waiters as a future customer, to editors and publishers as a prospective contributor. He provided what every child seeks most passionately from a parent- belief.

From my earliest days, he seemed possessed of superhuman powers to make exciting things happen. He got stars’ autographs, fixed meetings with comedians, privileged backstage visits to the circus. I didn’t then understand that these are the sort of petty perks which compensate journalists for lack of more substantial power and rewards. Once in a way, he took me to watch him broadcast from the BBC’s studios in Portland Place. I stood with face pressed against the glass wall of the control room, peering at his elegantly suited figure, addressing the microphone in impeccably-modulated tones. Mac attributed his beautiful voice to the Jesuits’ training in Rhetoric, for which he had won prizes at Stonyhurst. It is surely true that all children should be taught to speak, just as they are taught to write. The gift of self-expression is priceless.

From my earliest days, I was captivated by his gifts as a raconteur. There were lots of war stories, of course, told with the gusto which he brought to all his memories of 1939-45: how Monty stood by the dusty roadside in Normandy in August 1944, urging his armoured columns ‘On to the kill !’; how cocky captured German officers could be cut down to size by removing their jackboots; how he once ate a dog when rations were short. There were shooting yarns, fishing anecdotes, tales of journeys on the transatlantic Queens. He cherished a mass of potty prejudices- for instance, a suspicion of beards and bow ties, and a hatred for football, which he declared to be played by brutes for the amusement of other brutes. The unworthy thought didn’t then dawn on me, that the Hastings family’s dislike of ball games stems from our being so hopeless at them.

Father’s life seemed the pattern of what I wanted for myself, so that as soon as I started to buy my own clothes, I dressed in imitation of him. When I was old enough to choose holidays, I hurried to destinations which he loved, mostly Scottish. When I wanted to test myself against physical danger- which he persuaded me that every right-thinking Englishman should do- I addressed the same perils he had confronted, regretting only that the Germans were unavailable- temporarily, anyway- to play their usual forty-five minutes each way on the other side.

In only one way did he disappoint me. From an early age, I was a keen and rather credulous reader of P.G.Wodehouse, who formed my idea of how young English gentlemen behaved. One day, I asked father how often he had spent the night in jail after say, stealing a policeman’s helmet or being discovered dancing in the fountains of Trafalgar Square. He replied indignantly that he had never spent even an hour behind prison bars. This was a shocking blow to my image of him as a man-about-town.

I was equally awed by my mother, but in a different way. She was incomparably more realistic about me than father, making plain her fear that I was born to be hanged. From an early age, she treated me in the same fashion as did schoolmasters: as a habitual criminal rashly granted probation, but certain soon to reoffend. The evidence was on her side. She loved me sure enough, but in her determination not to succumb to foolish delusions, she expected the worst and usually got it.

She was dauntingly tall, six feet, the daughter of literary journalists, who won a classical scholarship from St.Paul’s to Somerville College. There, having attended London day-schools, she bitterly resented the confinement, under mediaeval rules designed to preserve chastity, which prevailed in womens’ colleges in the early 1930s. She wrote later:

Oxford was a good place for female swots with their minds concentrated on their degrees, and doubtless for lesbians, although I never consciously met any. It was a tolerable place for the few who broke all the rules and led a heady mixed social life. For the others, it could be a lonely world, with every twinge of melancholy aggravated by the rain-washed spires, tolling bells, and miasmas from the river.

Like so many adolescents, Anne felt that somewhere in the city, wonderful things were happening to which she was not invited. Romance was impeded by the locking of Somerville’s gates at 10.30pm, which made it necessary for a girl to climb in over the wall, even if she had only been to the cinema. She wrote: ‘It was all so silly’. After taking a First in Mods, she decided to leave and start a career. This was 1933, the depth of the Depression, a bad time to look for work. Few girls then entered the professions or the City. A friend of her parents was a director of the biscuit makers, Huntley & Palmer. He agreed to see her, but said immediately at the interview: ‘We do not employ women, Anne, except at factory level, and we have no present intention of doing so. Women aren’t good at business, and it wouldn’t be fair on the men’. Anne asked: wasn’t there the humblest opening in the office ? ‘No, only in the factory and that leads nowhere. Your mother tells me you went to Oxford. Frankly, that’s a disadvantage. There is no room in industry for educated women. The men don’t like them’.

Only after many struggles and disappointments did Anne at last find work on Vogue magazine. She worked there enthusiastically until in 1941 she became the first woman’s editor of Picture Post, of which my father was war correspondent. Mac fell in love with Anne almost on the first day he saw her. He told colleagues: ‘I’m going to marry that girl’, and set about besieging her with characteristic panache. That summer, he invited her to contribute to a weekly BBC radio broadcast which he made throughout the war to America. Here is how he introduced her, in an open love letter across the air waves: ‘When I’ve been blundering about trying to write from time to time on matters of feminine interest, I’ve often thought that what this column needed was the whisper of the petticoat and imprint of a lipstick. So this week, I’ve asked one of my most charming colleagues to end this London Letter. To introduce her, she looks as if she’d just stepped out of an advertisement. She has got a peaches and cream complexion such as men talk about and women envy. She knows more about American men than I do about American girls. She is as high as my heart, or higher, and the nicest girl that ever held a man’s hand under such a Bomber’s Moon as I’ve been writing about. Meet Anne Scott-James….’

Anne’s piece which followed was about her garden: ‘I’ve been bitten by the gardening bug. At lunch with my girlfriends, I discuss not hats, not jobs, not books, not even men…but cauliflowers, blackfly and the horrible disease called Big Bud. At first, the beauties of gardening clothes helped to egg me on. I liked myself in dungarees, in corduroys, in linen shorts, and striped aprons. I liked the shiny feel of a new trowel and quiet competence of new scissors. But now my motives are purged of vanity. I garden for the pure pleasure of digging and sowing and planting and pruning and staking and weeding- and picking and eating. I glory in a ruler-straight row of peckish young lettuce plants. I love my lupins. A pleasant thing, I think, that in the whirl of war we’ve rediscovered the excitement of making things grow’.

In 1945, shortly before I was born, Anne became editor of Harper’s Bazaar, and later a newspaper columnist, notably for the Daily Mail. Through my childhood and later that of my sister, she was a working woman at a time when combining motherhood with a career was an even harder balancing act than it is today. I find it easy to understand why Mac married Anne. She was beautiful, clever, witty, effective, a merciless realist. She claimed to like the country life so dear to his heart. It’s harder to see what Anne saw in Mac. For all his gifts and charm, he was a fantasist of heroic proportions. She gained an early clue to his priorities when, soon after they were married, she heard him say loudly at a party: ‘I’ve got the three things I wanted most- a Churchill gun, a Hardy fishing rod and a beautiful wife’. She wrote: ‘I strongly resented being counted as a chattel with a gun and a rod, and retreated more and more into my private thoughts’. Mac enjoyed the idea of living with a clever woman, but he had no intention of changing his habits, to help Anne towards fulfilment of her own ambitions and needs.

As a child, in my irritation about mummy’s daily absence, I lacked any understanding of the difficulties which every working woman then faced. The more significant her professional role, the greater the dilemmas. Her generation were pioneers, and suffered fearfully in consequence. As she left in the morning, I pleaded:

‘Mummy, try and get back for tea’, adding resignedly, ‘but I know you’ll be late. Shall I see you in my bath ? Anyway, mind you’re home before I go to sleep’.

Nanny said: ‘Now, do be early, today, madam. We’ll keep you a meringue till half-past five, and not a minute after’. But half-past five found madam with a queue of people still waiting outside the editor’s door, and letters to sign. She recorded later the spasm of regret which she experienced as she thought: ‘Bang goes my meringue’, and everything which it stood for. She described a typical schedule on days when she accompanied us to do clothes shopping:

2.00 Buy Chilprufe vests and Shetland cardigan at Hayfords.

2.45 Winter coat and leggings, Debenham & Freebody

3.30 Business appointment in Grosvenor Street. Nanny and Max

wait in car reading Peter Rabbit.

4.0 Socks, shoes and blouses at Harrods. Nanny pays while I

hurry to telephone couturier who is only in between 4 and

4.30, when he leaves for America.

4.30 We divide forces. I take a taxi back to the office, and send Nanny and Max home in the car.

Likewise on birthday party days, her notebook was scribbled with memos to herself about a confusion of matters professional and domestic: ‘Speak printers re May colour pages. Write April lead. Plan 2-colour section for June. Order birthday cake at Green Lizard. Twenty-one presents, 12 boys, 9 girls. See Judy about photographing Oliviers for New York. Candles, balloons, records, Nuts in May and Mulberry Bush. Fix advertising meeting. Separate table for nannies ?’ When party day came, there was always a phone call from her secretary in the midst of Happy Birthday:

‘I won’t keep you five seconds, Miss Scott-James. There’s a cable in saying will you be in Paris the first collection week or the second. What shall I say ?’.

‘Better say the second week’.

At summer holiday time, mummy usually drove us down to Devon, Cornwall or whatever other little paradise had been booked. She stayed through the first couple of days, then raced back to the office, leaving me on the sands with nanny, and later my sister Clare. Anne wrote:

‘I found those lazy days by the sea piercingly sad. Perhaps because the English summer is so short, there is always a dreadful nostalgia about a summer’s day, marguerites and poppies in a dusty field, or white cliffs throwing long evening shadows. In your mind, your child’s mind becomes all mixed up with your own, and the pathos of innocence become an agony which keeps the tears welling in your eyes. I used to sit half-choking on the beach as I watched that touching back view: little Max in blue mackintosh waders hand in hand with stalwart Nanny, both paddling inch-deep in the tiny breakers of low tide, Max clutching a hopeful bucket in his free hand, Nanny holding up her skirts above her varicose legs.

‘Oh God, make it last, make it last for ever’, you mumble mournfully. But hell and damnation, you are driving up to London late tonight and coming back for just one day to fetch them. It is not the mild regret of leaving any ordinary pleasant occasion; it is the splitting of the heart, the butchery of one’s own youth.

‘Mummy, mummy, watch me cut a crab in half’, calls Max from the water’s edge. He, at least, was not troubled by sentiment’.

Yet by Anne’s own admission, like so many clever women her emotions were confused about how long her patience could have endured the simple pleasures of sandcastles and West Country teashops. She sobbed through the first few minutes of her lonely drive home, but found that as the miles went by, her mind began once more to turn, and then to race, about her beloved magazine. She was planning a new feature as she reached Hammersmith, ‘tossing it about in my mind as in a butter-churn’. She thought: ‘I must phone Frances tonight and get her to chew it over, and we’ll get started on it tomorrow’. By midday next day, she was again absorbed in her work. The tiny world of the nursery could never have satisfied her.

Today, this is all familiar stuff. But in Anne’s day, there was no accommodation, no pity for a woman who chose to try to do it all. She felt overwhelming social pressure to look like a ‘proper’ mummy as well as a committed magazine editor, and went through the motions with dogged, desperate deliberation. She tried to behave as mothers were supposed to behave, but the outcome resembled an amateur dramatic performance. All these years later, I sympathise with her dilemmas. Of course she deserved professional fulfilment. There is also the small point, that without her income my upbringing would have been incomparably less comfortable. But it was hard to see those things half a century ago, when mummy’s impatience with Happy Families was manifest, her sophistication sorely tried by bedtime stories. Though she liked to perceive herself as a shy, fawnlike slip of a girl, in truth she possessed the habit of command, an absolute intolerance of fools, and some of the attributes of a Sherman tank. She inspired respect and fear, but uncertain affection.

She seemed to me a pattern of glamour and fluency, never less than flawlessly turned-out, seldom at a loss for the mot juste, sometimes pretty acid. I often attended mummy’s bedside early in the morning, where she sat surrounded by newspapers, telephone and breakfast tray prepared by our faithful London daily. There was the ritual of telephoning Harrods, to provide a list of groceries for delivery. In those its elegant pre-Fayed days, I grew up imagining that it was natural to buy everything from stamps to underclothes, writing paper to toys, at the great Knightsbridge palace. We met in its banking hall, my hair was cut in its barber’s shop, tea happened in its restaurant, school uniforms were ordered from its menswear department. The delusion that Harrods was the only possible place for a right-thinking London household to do its shopping later caused my first financial crisis, when I tried to maintain the habit from my own bank account.

We lived in a flat in Rutland Gate, beside Hyde Park. The parks’ congregation of nannies formed the hub of upper-middle class social life. Invitations to the round of little tea parties in Montpelier Square, Hans Place, Victoria Road were arranged between respective childrens’ custodians, rather than through parents, on the benches beside Rotten Row, or at Miss Ballantine’s famous dancing classes for posh toddlers in Brompton Road. It was nanny who, for a time, propelled me up the social ladder into the world of get-togethers at the Hyde Park Hotel with little gold chairs and pass-the-parcel; conjurers and dainty sardine sandwiches; sailing boats on the Round Pond; ‘tiddlers’- sticklebacks- brought home in jamjars and preserved until their smelly expiry; relentless tours of the Kensington museums.

Like almost every child of my time and lifestyle, I adored nanny. She came to us when I was six weeks old and stayed for eighteen years, through good times and bad. Her name was Jessie Strafford, and she was already approaching sixty when she signed on. One of eight children of the timekeeper at a Sheffield steelworks, she was Yorkshire through and through, unfailingly clad in grey overalls and sensible round blue felt hat. A comfortably heavy figure, she possessed what Anne described as ‘that flat-footed pram-pusher’s stance’. She was ‘square of figure and a doughty trencherwoman’. I adored nanny because she spoilt me rotten. My will was much stronger than hers. Discipline was entirely lacking. It required years of marriage for me to learn much later some basic manners which I should have acquired in the nursery, if I had been a more receptive pupil, and nanny less malleable.

Nanny didn’t like all children- indeed, she was balefully sceptical of most. She would say to my mother: ‘That little Henry Johnson doesn’t seem very sharp, does he ?’; ‘I wonder if young Pamela Croome will grow any bigger, madam ?’

‘Heavens, nanny, what a sinister idea. Why ever shouldn’t she ? She’s only eight months old, isn’t she ?’

‘Nine months, madam. And hasn’t put on an ounce for eleven weeks. I should be very worried if I were Lady Croome’.

Nanny’s affections were engaged only by her own charges, to whom she was single-mindedly devoted. There had been very few of these. When nanny joined a family, she stayed until the children were old enough to enter Sandhurst, ‘come out’ or take over the estate. She was a true imperialist, who after starting ‘in service’ as a nurserymaid at the age of fourteen had laboured for years under broiling sun in India and Ceylon with an Indian Army colonel; in Kenya under a governor-general; in Trinidad, the West Indies, Egypt and like outposts of British might with other proconsular dignitaries. Her conversation was studded with timeless nursery clichés: ‘Who got out of bed the wrong side this morning ?…A stitch in time saves nine…There’s no tea for Mr.Crosspatch…Has the cat got your tongue ?…Eat your toast crusts and make your hair curl…Wear clean underwear- you might get run over’. She was a fount of stories about the inadequacies of black servants, tiresome domestic intrusions of zebras, perils of drink, sterling qualities of the Tommy. At bathtime, she regaled me with snatches of old musical hall songs, almost invariably imperialistic: ‘Goodbye Dolly, I must leave you, though it breaks my heart to go’.

As my father grew older, his eccentricities became more dramatic. Three Hastingses- Mac, Anne and me- have at different times featured as guests on Desert Island Discs. Mac possessed unique credentials. He had himself experienced life as a castaway, albeit a voluntary one. It was the climax of his unflagging and often crazy pursuit of adventure. In the summer of 1960, he was pressed for money, desperate to make a coup to rescue him from the insistent clamourings of the Inland Revenue. His relations with Anne had become pretty wretched. He was seized by a yearning for escape, a breathing space. Most people in that state go walking in the Lake District or catch a boat to Le Touquet. Mac chose to have himself marooned on an uninhabited island in the Indian Ocean, equipped only with a gun and a hunting knife.

My own farewells to him were nonchalant, because his departures had become so familiar. My faith in his powers was unbounded. I responded to news that he was leaving for a desert island much as Superman’s son, if he had one, would have received news that dad was off for another bout with Lex Luthor. At 14, I saw Mac’s desert island adventure just as one more chapter in the epic of his life, one more giant obstacle on the assault course which I myself must some day undertake, to live up to his awesome achievements. It was years before I realised that the ideal journalistic stunt should look uncomfortable and dangerous, without being too much of either.

In father’s five lonely weeks on his atoll, he contracted jungle sores and scurvy, and almost starved to death. He returned to London on a stretcher, closely resembling as an ex-Japanese prisoner of war, entirely as a result of his own efforts. His experience represented the antithesis of Get Me Out of Here, I’m a Celebrity !. He exchanged appalling suffering for relatively modest reward. His health never entirely recovered. He wrote ruefully at the end of his account of the ordeal: ‘I’m sorry I did not do better’. His experiment did not prove that it was impossible for a castaway to survive on an atoll in the Indian Ocean. It merely showed that one as ill-prepared and impractical as himself was unlikely to fare very well.

Forty-five years later, a senior executive of the Daily Mail telephoned me bright and early one summer morning, to announce excitedly: ‘We’ve just had a marvellous idea ! You must go and relive your father’s desert island adventure’. I said: not a chance.

‘We’d pay you lots of money’

‘There is not enough in Lord Rothermere’s piggy bank to induce me to do anything of the sort. I’m fifty-nine, for God’s sake ! Father was fifty, and that was twenty years too old’. My disappointed caller put down the phone, to go off and tell his editor they were no longer making Hastingses like they used to do. I mopped my brow, reflecting thankfully on the lessons I’d learned since 1960. I revered father’s memory no less in 2005 than I had in my teens. But I realised that the most charitable verdict on his desert island nightmare was a plea of diminished responsibility.

During father’s married life, I doubt if he went in for much sexual misbehaviour. His excesses were committed, instead, with guns. He was potty about them, and I suppose it wasn’t surprising that I became infected by the bug. I found explosives irresistible. Father possessed large reserves of gunpowder for his 19th century flintlocks. These offered a child of an inquiring disposition lots of scope for experiment, and I achieved some impressive bangs. One day out from prep school, as we walked into the cottage father drew my attention to a large collection of fireworks. These, he said, were assembled for a forthcoming party with his club friends. On no account was I to touch them. I spent the next hour in my bedroom, dissecting the biggest rocket. Curiosity then prompted me to apply a match to its heaped entrails. For some hours afterwards, fearful of recriminations, I concealed the frightful burns on my hand until, in the midst of tea, pain became unbearable and I burst into tears. I returned to school in heavy bandages and disgrace. Any sense of guilt was moderated, however, by learning that a week later that father and his club friends, liberally oiled, had burnt half the thatch off a nearby cottage roof while participating exuberantly during their firework display.

Whenever the parents were safely absent and I was left to my own devices under nanny’s unseeing eye, I got out some of his guns and blazed away on the lawn. I grew increasingly ambitious. In an oak chest in father’s room, father kept his war souvenirs- a clutch of automatic pistols and ammunition. At first, I confined myself merely to stripping and reassembling the guns, at which I became an exceptionally proficient 11 year-old. Soon, inevitably, I dared to fire them, emptying a Luger magazine into the garden seat. I sometimes invited a few friends round for tea, cucumber sandwiches and pistol practice. They giggled nervously amid the cannonade and later, I suspect, told their parents. Playmates became increasingly unwilling to accept invitations. A local view gained currency that the Hastings family, always known to be mad, were also bad and dangerous to know.

Nanny was oblivious of my games with guns, but my mother was dismayed by rumours. Word swept the family, that on father’s return from his latest foreign assignment, all the World War II weapons would vanish. Appalled, I chose my favourite pistol and secreted it in the luggage when we returned to London from the cottage. An evening or so later, I was sitting in my room in the flat watching an instalment of an American TV soap drama- Perry Mason, as it happened. Most of my attention was on the screen, but as I viewed I caressed, stripped and reassembled the pistol, pushed in an ammunition clip, and snapped the gun at the screen. Mother, more than forty years later on Desert Island Discs, was very unjust to me in suggesting that I got over-excited watching a Western. It wasn’t a Western. What happened was the fruit of momentary carelessness, such as could befall- well, any male member of the Hastings family.

I remember as if it were yesterday the spectacle of the TV disappearing in a sudden eruption of smoke and cascade of glass, with much tinkling and clatter. I was so surprised by the effect, as was unavoidable on hearing a gunshot at close quarters in Cromwell Road, that I slumped back in my chair, pistol dangling limply in my hand. This caused Mummy, rushing in seconds later, to assume the worst. I reassured her that everything was fine with everything except the unfortunate television. Should you to be thinking of firing a pistol in a Victorian mansion block, and wonder whether the noise would bother the neighbours, I can reassure you. Nobody else in our flats complained about a thing. Even by the standards of our family, however, the ensuing row was a corker. I remained in disgrace for weeks, as indeed did father. It wasn’t long after that episode that mother decided enough was enough, and gave Mac his marching orders. They were divorced in 1962, and our tumultuous family circle broke up. Thereafter, Anne married the artist and cartoonist Osbert Lancaster, and forged a notable second career as a gardening writer. Mac’s eccentricities remained undiminished until his death in 1982, but after his own remarriage to his publisher’s widow he achieved a contentment unsullied by any more dramas or adventures.

In mother’s old age, I told her I could easily understand why she divorced father, but I couldn’t for the life of me imagine why she married him in the first place. She brooded for a moment, then said: ‘Lots of people married the wrong people in the war. Your father cut quite a romantic figure in battledress’. Another pause: ‘And I was stupid enough to think he might be a good parent to children’. For years, I was unjustly bitter towards her about our fractured and fractious family life. But one of the best things about oneself becoming middle-aged is that one stops being jealous of other people. Almost all of us come simply to be deeply grateful for what we have got. My admiration for dear, batty father never diminished. But I learned to value my mother’s remarkable gifts at their true value- and to perceive how lucky I was in my heredity. The old adage, that truth is the daughter of time, is quite mistaken. But at long last I grew up sufficiently to thank my stars for genes and upbringing- and my parents for the wonderfully rackety experiences of my childhood.