Warriors is an old-fashioned book, or at least a book about old-fashioned conflicts, because it’s about people rather than ‘platforms’, that unlovely modern phrase for tanks, ships, planes. I’ve written about 15 remarkable characters- some successes and some failures- who made their marks on conflicts of the past two centuries, and tried to explore what we can learn from them about human nature amid the changing face of war.

In ordinary life, people who like fighting are at best an embarrassment. Warriors are unfashionable when there isn’t a war on. Nelson liked to quote Thomas Jordan’s bitter little verse:

Our God and sailor we adore,

In time of danger, not before;

The danger past, both are alike requited,

God is forgotten, and the sailor slighted.

Yet in times of war, successful fighting men suddenly become celebrities- or at least did so until very recently. I chose my subjects to reflect a range of experiences and to provide entertaining bedside reading, but when I finished I was struck by how much some characters had in common. Several had bleak childhoods, which may have influenced the anger they carried with them onto the battlefield. Few sustained stable personal lives. Not many star warriors have been popular comrades. Like Achilles they are admired, but also feared by those with whom they serve. Soldiers, and especially conscript citizen soldiers, prefer to share a foxhole with men whom they recognize as made of the same frail stuff as themselves.

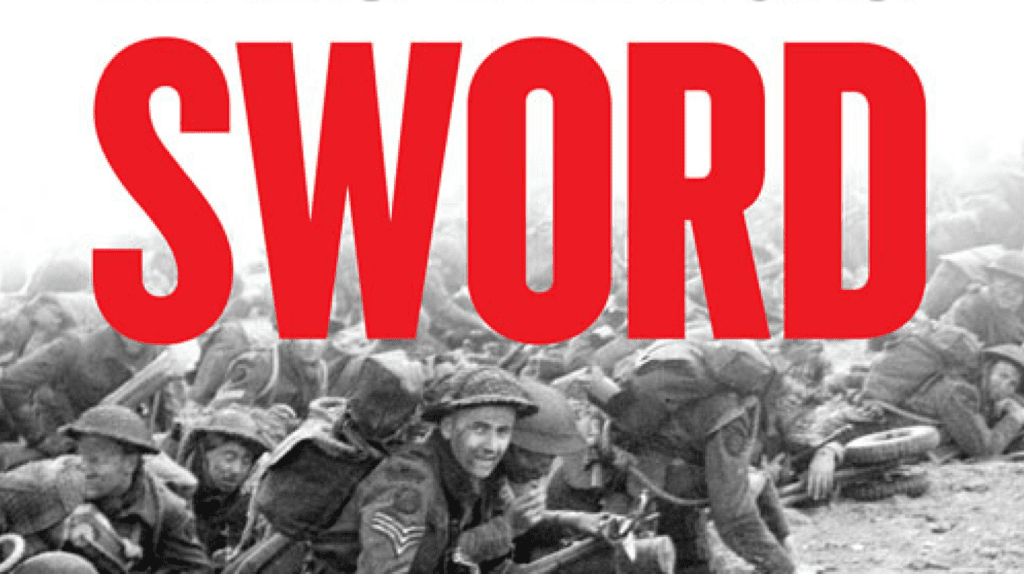

One of my favourite WWII stories concerns a sergeant-major of the Green Howards, Stan Hollis. On D-Day, 6 June 1944, and in the battles that followed, three times Hollis attacked German positions which were holding up his battalion’s advance. He charged them alone, killing or taking prisoner the defenders. Many years later, his commanding officer recalled for me the sergeant-major who miraculously lived to receive a Victoria Cross and keep a Yorkshire pub in old age. The colonel said: ‘I think Hollis was the only man I met between 1939 and 1945 who felt that winning the war was his personal responsibility. Everybody else, when they heard there was a bloody awful job on, used to mutter: ‘Please God some other poor sod can be found to do it!’’.

Every army, to prevail on the battlefield, needs a few people like Sergeant-Major Hollis, capable of courage, initiative or leadership beyond the norm. What’s the norm ? It has changed in the course of history. In the old days, a soldier’s belief in the nobility of his calling stemmed in part from accepting the risk of losing his own life, while taking those of others. It would be wrong to overstate the chivalry involved, because of course every warrior tried to kill his enemy while surviving himself. But acceptance of possible death, win or lose, was part of the warrior’s contract, in a fashion that has vanished today. Struggles with guerillas and suicide bombers inflict painful losses on Western armies. But if things go to plan in heavyweight operations like the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq or the bombing of Kosovo, the big battalions win with very few casualties. A lot of the losers get killed, but questions are asked in the House of Commons if there are significant casualties on our side. Any idea of parity of human risk is long gone. We are back to the rules of engagement that prevailed in many 19th Century colonial conflicts: ‘Whatever happens, we have got the Maxim gun and they have not’; or, in 21st Century language, ‘we’ve got body armour which will keep out bullets and tanks which will stop anything short of a missile’.

By contrast, in the battles of Bonaparte’s time, an infantryman was expected to stand at his place in a square, loading and aiming a musket usually without the protection of trench, while the enemy in his turn fired volleys at himself and his comrades from thirty or forty yards, hour after hour. The wars of Bonaparte went on for the best part of twenty years, so many veterans defied these terrors thirty, forty, fifty times. For a soldier to earn a reputation for bravery, he had to exceed a norm which any modern soldier would find unbearable.

The end of the nineteenth century marked the passing of a warrior ethic which had prevailed since earliest history, whereby battle was thought a proper amusement for the leisured classes, as well as a source of jobs for the poorest ones. As a war correspondent, Winston Churchill sounded a last hurrah for the gentleman adventurer in a typically exuberant dispatch from the Boer War in February 1900, when he was 25.

‘The soldier, who fares simply, sleeps soundly and rises with the morning star, wakes in an elation of body and spirit without an effort and with scarcely a yawn. There is no more delicious moment in the day than this, while we light the fire and, while the kettle boils, watch the dark shadow of the hills take form, perspective and finally colour, knowing that there is another whole day begun, bright with chance and interest. All cares are banished- for who can be worried about the little matters of humdrum life when he may be dead before the night ? Such a one was with us yesterday- see, there is a spare mug for coffee in the mess- but now gone for ever. And so it may be with us tomorrow. What does it matter that this or that is misunderstood or perverted; that so-and-so is envious and spiteful; that heavy difficulties obstruct the larger schemes of life, clogging nimble aspiration with the mud of matters of fact ? Here life itself, life at its best and healthiest, awaits the caprice of a bullet. Existence is never so sweet as when it is at hazard’.

Only a small number of soldiers enjoyed the conflicts of the twentieth century as much as Churchill revelled in his adventures. World wars inflicted such horrors upon mankind that it became unacceptable to treat them as entertainments. After the terrible experience of 1914-18 on the Western Front, there was a consensus among Anglo-Americans, anyway, that it was impossible again to make such demands upon soldiers. In World War II, commanders tried to use firepower rather than human endeavour, tolerated ‘combat fatigue’ as a recognised medical condition, and weren’t keen to persist with any operation that cost a lot of lives. We might suggest that ‘fanatical’ Japanese or German behaviour which roused the revulsion of 1939-45 American and British soldiers, was no more than had been asked as a commonplace of their own ancestors: a willingness to obey orders that were likely to get them killed. The norm had changed.

Yet in every society on earth, the most durable convention for thousands of years was that which held physical courage to be the highest human attribute. Bravery was valued more highly than brains or moral worth. AEW Mason’s classic adventure story The Four Feathers, set in 1898, is about a sensitive young army officer who resigns his commission because he prefers to stay in England enjoying country life with an adored fiancee, rather than go with his regiment up the Nile to slaughter Dervishes. His girl joins brother officers in offering him a white feather. He has to perform amazing feats of derring-do to recover her affections. Four Feathers always seems to me flawed, because the hero eventually has to marry this silly girl, who surely proved her unfitness as a partner for life by being so keen on brawn over brains, preferring to see her loved one risk killing himself, rather than indulge his poetic nature.

Yet The Four Feathers vividly reflected the values of its period. A consequence of mankind’s exaggerated regard for courage is that some remarkably stupid men, their only virtue a willingness to risk their necks, have been promoted to high commands. Bonaparte often over-promoted officers with a lot of courage and not many brains- I have told the story of one of these swashbucklers, the hussar Marcellin Marbot. Ambrose Bierce a century ago advised the ambitious warrior: ‘Always try to get yourself killed’. Many people who do this are, however, fools by any ordinary yardstick. Courage is a fine thing in a commander, but it’s usually fatal to the interests of his soldiers unless accompanied by a few brains. Brave fighters should be given lots of medals, but at all costs not promoted. Being good at killing people is a pretty limited gift, even for a warrior.

In the peaceful times in which we are lucky enough to live- with or without Al Q’aeda, our ancestors would think our age incredibly privileged- there is a yearning to make life safe. Most of the people whose stories feature in my book would laugh at our society’s quest for an existence without risk. They would be amazed by the increasingly widespread belief that if governments do their business properly, even a soldier in war can be protected from harm. It is surely a very good thing that popular ideas of courage no longer embrace only, or even chiefly, achievement in battle. But it seems dismaying that the media, and the public, today blur the distinction between a hero and a mere victim. The media, for instance, will describe a pilot who safely lands a crippled planeload of passengers as ‘a hero’. Yet such a man is simply a victim of misfortune. If he behaves well, he is doing so to save his own skin, and only incidentally those of other people. Anyone who has served in a theatre of war, even on a supply line and even in as bloodless an affair- from the allied viewpoint- as the 2003 invasion of Iraq, is likely to be described in any later press report of a divorce or car crash as a ‘war hero’. This is a travesty. We should preserve such a word as ‘hero’ as carefully as any other endangered species. To thoughtful people, a hero must consciously consent to risk or sacrifice his life for a higher purpose.

The warrior who deserves the highest respect is the one who does his deeds alone, without the help of the hugely powerful spur of comradeship. That great storyteller C.S.Forester wrote a wry little novel Brown On Resolution. It tells of a British sailor in the First World War, only survivor of a cruiser sunk in the Pacific by a German raider. Brown escapes with a rifle onto an uninhabited volcanic island, Resolution, where the German ship has put in for repairs. This stolid young man, schooled all his life to a simple concept of duty, knows that what he is doing must get him killed, but he accepts his fate unquestioning. By harassing the German warship from the shore, Brown delays its departure just long enough for a British squadron to engage and sink it with all hands. Brown himself is left mortally wounded, alone on his barren rock. For our purposes the point of Forester’s story is that no one afterwards knows what Brown did. This is a cautionary tale for warriors. The highest form of courage is that of a man who sacrifices his life without hope of recognition.

By contrast many acts of heroism, some recorded in this book, are committed in pursuit of gongs or glory. Eager warriors, aspiring heroes, are generally disliked and mistrusted by more normal men who have to serve with them. ‘It’s all right for him if he wants to win a VC’, they mutter, ‘but what about us ?’. I grew up to idolise Wing-Commander Guy Gibson, who led the 1943 RAF dam-breaking raid. I was amazed later to discover how much Gibson was disliked by some of those who served under him. ‘He was the sort of little bugger who was always jumping out from behind a hut and telling you your buttons were undone’, an air gunner once told me. After my piece on Gibson in Warriors was serialised, I was intrigued to get three letters from readers who served with him in Bomber Command. All said they used to find it a bit embarrassing that, while they respected him as a leader, they disliked him as a man.

No one doubted the bravery of Colonel H Jones at Goose Green in the Falklands War. But the recommendation for H’s VC came from Downing Street, not from the army. Many soldiers argued that Jones’s action in charging personally at the Argentine positions was the negation of the duty of a battalion commander, and reflected the fact that H had lost control of the battle. He was a fiercely emotional man, fired by a heroic vision. Many soldiers prefer to be led by cooler spirits.

A cynic might say that some eager warriors are exhibitionists of an extreme kind, prepared to risk their lives to gain attention. A cynic would be right. This doesn’t make warriors less worthy of our respect, but might make us a bit more sceptical about their motives. ‘Adventure has always been a selfish business’, Peter Fleming once wrote. ‘The desire to benefit the community is never [adventurers’] principal motive…They do it because they want to. It suits them; it is their cup of tea’. The same is true of eager warriors. Take Colonel Fred Burnaby, a passionate sensationalist who was finally killed in January 1885, at Abu Klea on the doomed Gordon relief expedition. As the battle ended, a comrade named Lord Binning ran to the spot thirty yards beyond the square where Burnaby lay, his life’s blood draining away, in the arms of a young soldier: ‘Oh! Sir’, cried the trooper, ‘here is the bravest man in England dying, and no one to help him’. Binning took his colonel’s hands, felt a feeble pressure and saw a faint look of recognition, before Burnaby was gone. ‘His face’, wrote Binning, ‘bore the composed and placid smile of one who had been suddenly called away in the midst of a congenial and favourite occupation; as undoubtedly was the case’.

Yet in every war, a small minority of natural warriors like Burnaby fights alongside many other men who threaten their own army’s chance of victory by being keen to stay alive. Macaulay’s Horatius asked: ‘How can man die better than facing fearful odds, for the ashes of his fathers and the temples of his gods ?

The trouble from a commander’s viewpoint, however, a dismayingly small number of men share Horatius’s attitude. Most don’t want to die. This is why commanders find it useful to provide soldiers with incentives, in the form of intrinsically worthless discs of crosses of metal. Many decorations are awarded for acts of courage. But others are dished out chiefly for political reasons There was a lot of cynicism in the British Army, for instance, about the 11 VCs awarded for the 1879 defence of Rorke’s Drift- a story I’ve recounted in the book. Disraeli’s government pounced on this heroic little episode to make everyone feel better about the much bigger disaster a few miles away the same morning, when an entire British battalion had been wiped out by the Zulus at Isldwhana. Commanders like Sir Garnet Wolseley were furious at the shower of decorations the politicians made them hand out for Rorke’s Drift. Even some of the defenders of the mission felt the same way. Private Robert Head sat down after the battle and wrote with the stump of a pencil to his brother in Capetown:

‘I daresay you will have seen in the paper before you receive this we under Leuit Chard and Bromhead had a nice night of it at Rodke’s Drift I call it I never shall forget the same place as long as I live I daresay the old Fool in command will make a great fuss over our two officers commanding our company in keeping the Zulu Buck back with the private soldier what will he get nothing only he may get the praise of the public…I am jolly, only short of a [pipe] and bacca, your loving brother Bob Head’.

Here was the authentic, immortal voice of the British private soldier. Many warriors who achieve great things as young men say later in life that nothing remotely as stimulating or interesting happened to them afterwards, which has often been a cause of sadness. Having achieved fame- sometimes together with authority and responsibility- at an age when most people in peacetime are mere students or apprentices, old age offers many veterans sour fruits. Every schoolboy learns the words Shakespeare wrote for Henry V on the morning of Agincourt in 1415:

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day’.

Contrast that glorious prophesy with the petition of an authentic Agincourt veteran to the authentic Henry VI in 1429:

‘To the King, our sovereign lord,

Beseecheth meekly your poor liegeman and humble petitioner Thomas Hostelle…that in consideration of his service done to your noble progenitors of full blessed memory, King Henry IV and King Henry V, being at the siege of Harfleur there smitten with a springbolt through the head, losing his one eye and his cheek bone broken; also at the battle of Agincourt, and afore at the taking of the carracks on the sea, there with a gadde of iron his plates smitten into his body and his hand smitten in sunder, and sore hurt, maimed and wounded, by means whereof he being sore feebled and bruised, now fall to great age and poverty, greatly indebted, and may not help himself…and being for his said service never yet recompensed nor rewarded, it please your high and excellent grace…of your benign pity and grace to relieve and refresh your said petitioner as it shall please you..’.

History doesn’t record the fate of Hostelle’s petition, but it is hard to be optimistic. Many successful warriors have found themselves sorely neglected once the shooting has stopped. Kipling wrote in 1891:

There were thirty million English who talked of England’s might,

There were twenty broken troopers who lacked a bed for the night.

They had neither food nor money, they had neither service nor trade;

They were only shiftless soldiers, the last of the Light Brigade.

The commanding officer of the British battalion in which Sergeant-Major Stan Hollis served on D-Day wrote sadly 40 years after: ‘I am afraid it was easier to get Hollis a VC in the war than a decent job after it’. Yet for all the warrior’s social limitations and vanities, we should continue to honour men willing to risk everything on the field of battle, and sometimes to lose it, for purposes sometimes selfish or mistaken, but often noble. Even the most civilized societies should take pride in the military heritage which through the centuries has secured their prosperity, and sometimes their survival. Kipling again:

We aren’t no thin red heroes, nor we aren’t no blackguards too,

But single men in barricks, most remarkable like you;

An’ if sometimes our conduck isn’t all your fancy paints,

Why, single men in barricks don’t grow into plaster saints;

While it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ ‘Tommy, fall be’ind’,

But it’s ‘Please to walk in front, sir’, when there’s trouble in the wind.

I’ve tried to tell the tales of some warriors who walked in front when there was trouble in the wind. Few of us could emulate them, or wish to, but their stories will continue to fascinate posterity, especially at such a moment as this 60th anniversary of World War II’s VE Day, as examples of all the things we, in our generation, are so deeply fortunate to have been spared.